As the war in the Pacific Theater progressed, the U.S. ramped up strategic bombing operations against Japan applying the same tactics employed over occupied Europe – daylight precision bombing of war related industrial complexes with high explosive ordnance. During 1944 the campaign wreaked havoc among industry and forced the Japanese people to alter their lifestyle. The campaign however had failed to accomplish its stated goal of obliterating all wartime production facilities.[1] Japanese war production managers had very cleverly dismantled many large factories and hidden them in civilian neighborhoods where they would be almost impossible to pinpoint.

When General Curtis LeMay took over command of the U.S. Army Air Force’s B-29s based in the Mariana Islands in January 1945 he set about to remedy the issue with an entirely different approach. Faced with the fact that two thirds of all Japanese war production had been spread out in cities in small neighborhood factories of thirty employees or less, LeMay realized that the USAAF would have to change its tactics to be successful.[2]

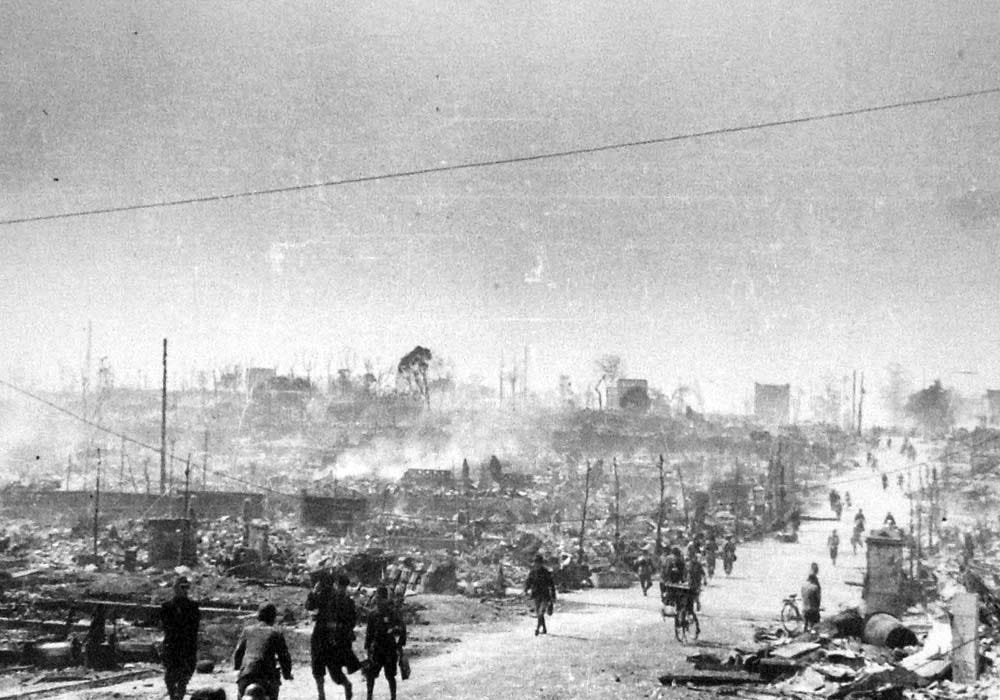

Orders were cut for a March 9, 1945, mission against the Japanese capital of Tokyo – orders that most airmen considered suicidal. Not only would they approach the target at the unheard-of low altitudes of 8,000 feet or less, but they would also be required to strip all machine guns and ammunition except for the tail gunner to increase the bomb payload.[3] Instead of carrying high explosive bombs the planes would be loaded to maximum capacity with incendiary bombs designed to scatter hundreds of smaller bomblets over a large area. Most of the structures in Japanese cities were wooden. The plan – burn them all to the ground. When the first wave of B-29s reached their targets over Tokyo they simply released their payload over areas that pathfinder aircraft had marked with napalm bombs. They were met with light anti-aircraft fire and no enemy fighter cover. In only minutes the city’s center became a raging inferno over 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit.[4] Asphalt streets and glass melted in the heat. Hurricane force winds fed the flames that shot thousands of feet into the sky creating a glow that could be seen from miles away and which would guide subsequent B-29 formations to their target. Over the target B-29s crews were buffeted by thermal updrafts which carried the scent of burning wood and human flesh.[5] The overpowering odor penetrated the low-lying aircraft and caused some crewmen to vomit.[6]

The results of the attack were just what LeMay was looking for and similar bombing raids were carried out immediately across Japan with devastating effect. In a period of only a few months many of Japan’s largest and most strategically important cities were nothing more than charred wasteland.

The dead were numbered in the tens of thousands. Japanese government records placed the number of dead at 83,793 with over 40,000 injured and over one million people left homeless just in the first firebombing of Tokyo.[7] Over 8.5 million city-dwelling Japanese civilians were eventually made homeless, including the royal family, and twenty percent of all Japanese civilian dwellings had been destroyed (by comparison fifteen percent of all German dwellings were destroyed during four years of round the clock Allied bombing).[8]

Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at the time…. I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal… every soldier thinks something of the moral aspects of what he is doing. But all war is immoral and if you let that bother you, you are not a good soldier. General Curtis LeMay

The raids depleted already dwindling clothing, medical, and other supplies in the island nation as stockpiles went up in flames in large wooden warehouses. Transportation came to a standstill in many cities and food became scarce. Unemployment skyrocketed to over fifty percent in some areas.[9] After the war the U.S. Army Air Force Strategic Bombing Survey determined that in Tokyo alone over 25,000 small factories employing less than 100 employees each were either destroyed or badly damaged.[10] The same survey found that Japanese war production depended heavily on these small subcontractors. The attacks were fatal to whole industries, aircraft manufacture, for example, would never recover.[11]

The strategic bombing campaign of 1945 not only decimated Japanese wartime production it also prompted the formation of a peace coalition. Emperor Hirohito on various occasions, against the counsel of his advisors, had toured bombed areas of Tokyo after the March 9, 1945 raid and seen the suffering and destruction of his people with his own eyes.[12] The American invasion of Okinawa facilitated the creation of a new Japanese government which included Japanese statesmen who wanted peace (Suzuki, Kido, and Konoye) and who understood the emperor’s desire to end the war as soon as possible.[13] As a result peace feelers were extended even before the dropping of the first atomic bomb. Unfortunately, the doves in Hirohito’s cabinet were outnumbered by hawks who would rather see Japan commit national hari-kiri before surrendering. These men believed that surrender would destroy Yamato Damashii (Japanese national spirit) and Kokutai (sovereignty of the emperor) and that it was correct to defy the emperor’s desire for peace, as it was a mistaken and ill-advised judgment; in their mind true faithfulness to the emperor made temporary disobedience imperative.[14]

The Japanese military amassed a force of fifty-three infantry divisions and twenty-five brigades (a total of 2,350,000 men) to meet the expected Allied invasion force at the beach.[15] They would initially be backed by a force of over four million soldiers and civilians. Eventually this force was expanded to include every able-bodied man from the age of fifteen to sixty and every woman from seventeen to forty five.[16] Even after the dropping of the atomic bombs Japanese warhawks in the cabinet refused to consider surrender as an option until Emperor Hirohito broke tradition and expressly ordered them directly, and in no uncertain terms that he desired “...that all of you, my ministers of state, bow to my wishes and accept the Allied reply forthwith.”[17] Even after the emperor demanded that the government surrender unconditionally there were those who revolted and came close to sabotaging the peace effort.

References

[1] John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945 (Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition, 2003), Kindle Locations 15182-15183.

[2] Ibid. Kindle Locations 15187-15188.

[3] Ibid. Kindle Locations 15188-15192.

[4] Ibid. Kindle Locations 15225-15226.

[5] E. Bartlett Kerr, Flames Over Tokyo: The U.S. Army Air Forces' Incendiary Campaign Against Japan 1944-1945 (New York, NY: Donald I. Fine Inc, 1991), 182.

[6] Toland, Kindle Locations 15256-15259.

[7] Kerr, 207.

[8] Ibid. 281.

[9] Ibid. 280.

[10] Ibid. 279.

[11] Ibid. 278-279.

[12] Ibid. 284.

[13] Ibid. 284-286.

[14] Toland, Kindle Locations 18332-18335.

[15] Ibid. Kindle Locations 16944-16951.

[16] Ibid. Kindle Locations 16948-16951.

[17] Ibid. Kindle Locations 18609-18613.