The Malmedy Massacre stands as one of the most infamous war crimes committed during World War II. Eighty years ago today, on December 17, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge – the largest and bloodiest battle fought by the Allies on the Western Front – soldiers from the Waffen-SS carried out the execution of American prisoners of war (POWs) at the Baugnez crossroads near Malmedy, Belgium. The massacre, which resulted in the deaths of 84 U.S. soldiers, highlighted the brutal and indiscriminate violence that marked the closing months of the war. However, the Malmedy massacre was not a unique event – it was part of a broader pattern of atrocities carried out by the Third Reich's Waffen-SS, a force infamous for its brutality and ruthless tactics.

In this post, we will explore the details of the massacre at Baugnez crossroads, the fate of its victims, the investigation that followed, and the consequences of this horrific event. Additionally, we will examine the role of retaliation by the Allies and the subsequent coverup that sought to obscure some of the war crimes committed by American forces during the Battle of the Bulge.

The Baugnez Crossroads Massacre

The Malmedy Massacre occurred during the Ardennes Counteroffensive, launched by German forces in December 1944 as a last-ditch effort to reverse Allied advances in Western Europe. The offensive aimed to penetrate the Allied lines, capture key locations, and ultimately split the U.S. and British forces, creating confusion and securing a victory for Nazi Germany. The Ardennes Offensive became known as the Battle of the Bulge due to the "bulge" in the Allied front lines caused by the German advance.

The specific massacre at the Baugnez crossroads, located two miles southwest of Malmedy, unfolded in the early afternoon of December 17, 1944. Kampfgruppe Peiper, the armored spearhead of the 6th SS Panzer Army, led by SS-Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Joachim Peiper, was tasked with rapidly punching through the U.S. defenses and seizing key objectives. At Baugnez, a convoy of U.S. Army vehicles from B Battery of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, attempting to head westward towards Ligneuville and St. Vith, unexpectedly ran head-on into advance elements of Peiper’s Waffen-SS force.

As the convoy made its way through the crossroads, the German armor opened fire, destroying the lead and trailing vehicles. Mounted in jeeps and trucks, the smaller and lightly armed U.S. force was no match for the heavy SS tanks. Surrounded, outnumbered, and outgunned the American GIs surrendered. The Waffen-SS, who had little regard for the Geneva Conventions or the rights of prisoners of war, marched the POWs into a nearby farmer’s field, and ordered them stand in close order formation. There, at the signal of the SS officer in charge, German soldiers methodically executed them with machine guns, shooting many at close range. Panicked survivors either fled or lay motionless, pretending to be dead.

Several survivors later recounted the horrifying scene. Some U.S. soldiers managed to hide in nearby buildings, only to be discovered and executed by the SS troopers. Among these was a café, at the Baugnez crossroads, which the Germans set on fire, killing those who had sought refuge inside the establishment along with its proprietor Madame Bodarwé.

The aftermath was devastating. Of the 84 U.S. POWs, only a handful survived by laying still in pools of blood. The dead were left in the snow-covered field. To the Americans, the massacre at Baugnez became emblematic of the brutality that defined their Nazi enemy.

Video above contains German combat footage of 1st SS Panzer Division advancing in Belgium. At 0:42 Kampfgruppe Peiper troops are seen passing roadsigns toward Malmedy.

Victims of the Massacre

The 84 American soldiers who lost their lives at Baugnez represented various units from the U.S. Army. They came from different backgrounds and had endured the grueling conditions of the war, only to fall victim to the brutal methods of the Waffen-SS. These men had been part of a convoy of artillery observers and soldiers tasked with supporting the U.S. 7th Armored Division. Among them was 1st Lt. Virgil Larry, the only officer who managed to survive the massacre and later testified to the atrocities.

A bullet went through the head of the man next to me. I lay tensely still, expecting the end. Could he see me breathing? Could I take a kick in the groin without wincing?... He was standing at my head. What was he doing? Time seemed to stand still. And then I heard him reloading his pistol in a deliberate manner...laughing and talking. A few odd steps before the reloading was finished and he was no longer so close to my head, then another shot a little farther away, and he had passed me up.

1st Lt. Virgil T. Lary, Jr., Executive Officer, B Battery, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion

Many of the soldiers captured at Baugnez were young, with most in their early 20s. They had enlisted to fight for their country, many of them barely out of their teens. Despite the desperate circumstances they found themselves in, these men posed no threat to the SS troops who captured them. Yet, the German forces, vanguard of the 6th SS Panzer Army, were behind schedule and not about to be hindered by a gaggle of prisoners. So, they handled the situation as they would have on the Eastern Front where wanton murder of POWs by both sides was a normal occurrence.

In the aftermath of the massacre, the bodies were recovered and documented by U.S. investigators. Forensic examinations revealed the gruesome details of their deaths. Many had multiple gunshot wounds, especially to the head, indicating they had been summarily executed. Some of the corpses displayed gunpowder burns around the head, marking coup de grâce executions – meaning these soldiers were still alive when they were shot in the head at close range.

In addition to bullet wounds, autopsies revealed blunt force cranial trauma from rifle butts, underscoring the savage nature of the killings. The bodies of most of the U.S. soldiers were found clustered in a small area, indicating they had been gathered closely together and methodically killed, as eyewitnesses later confirmed.

Investigation and Evidence

Following the liberation of Baugnez in early January 1945, U.S. military investigators documented the scene of the massacre. Forensic teams took photographs of the snow-covered bodies, gathering evidence that would later be used in war crimes trials. The bodies of twenty U.S. POWs had gunshot residues on their heads, indicating they had been shot at close range; these were not self-inflicted wounds, rather they were cold blooded executions.

The discovery of this evidence, along with eyewitness testimony, was central to establishing accountability for the war crimes committed at Baugnez. The investigation clearly and unequivocally revealed how the Germans systematically executed the prisoners after capturing them.

Despite the overwhelming evidence, there was initially little urgency to investigate the massacre thoroughly and charge the perpetrators. At the moment, most in the U.S. high command were focused on defeating the German counteroffensive rather than prosecuting war crimes. However, as the extent of the massacre became known, it aroused outrage within the Allied forces. The Malmedy massacre trial, part of the Dachau Trials conducted from 1945 to 1947, sought to bring those responsible to justice.

WARNING - GRAPHIC. The video linked above contains footage of U.S. Army Graves Registration troops recovering bodies of American servicemen killed in the Battle of the Bulge. At 2:15 American troops unload bodies of Malmedy massacre victims from a truck and into a building. Troops then remove and document personal items from the corpses. U.S. Army footage filmed in January 1945. Public Domain.

Trial and Accountability

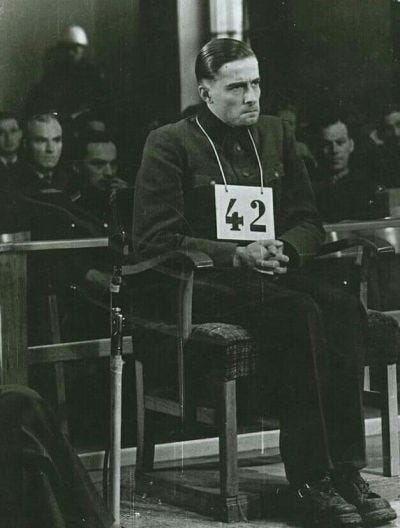

The Malmedy massacre trial, held in May-July 1946, was a pivotal moment in holding Nazi perpetrators accountable. Among those indicted were key figures from the Waffen-SS, including SS-General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, SS-Sturmbannführer (Major) Werner Poetschke, and SS-Obersturmbannführer Joachim Peiper. These men, along with others, were charged with murder and war crimes related to the massacre.

Poetschke, who was identified by witnesses as the likely officer who ordered the execution of the U.S. POWs, was accused of giving direct orders to subordinates to kill the prisoners at Baugnez. Peiper, while absent from the immediate scene of the massacre, was held accountable for creating a culture within Kampfgruppe Peiper that treated prisoners with contempt and encouraged brutal methods.

The trial sentenced several to death, including Poetschke (who had already died in March 1945 from wounds sustained in battle), but none of these sentences were carried out. Rather, all sentences were eventually commuted as an act of reconciliation. Peiper, despite being condemned, managed to evade the full consequences of his actions, being released from custody in 1956. Dietrich, despite his role as the commanding officer of the 6th SS Panzer Army, was also released in 1955. Peiper later fell victim to vigilante justice when he was assassinated by former French partisans in 1976 and his home burned to the ground.

While the trials did not result in the punishment of the guilty, they exposed the extent of Nazi war crimes and ensured that the atrocities committed at Baugnez and other locations were recorded for posterity.

Allied Retaliation and the Chenogne Massacre

The Malmedy massacre had a psychological and moral impact on the Allied forces. In response to the brutality exhibited by the Waffen-SS, some American units took retaliatory actions. One such event was the Chenogne massacre, which took place on January 1, 1945, during the Battle of the Bulge.

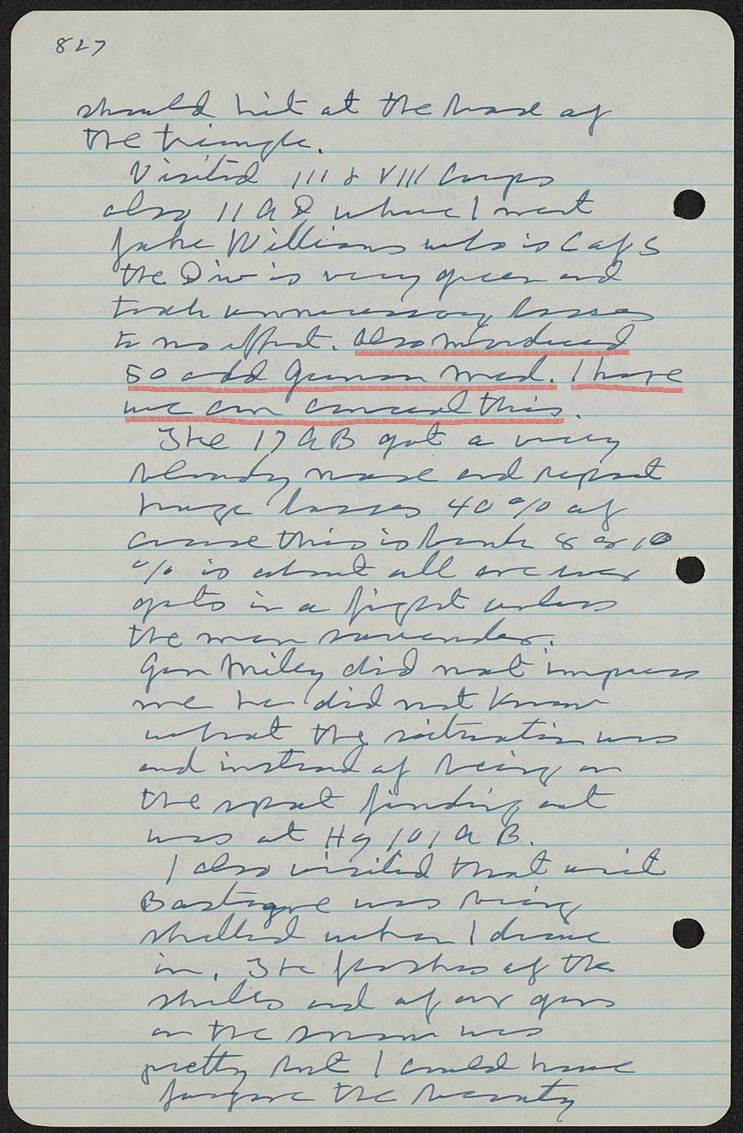

Near the Belgian village of Chenogne, American 11th Armored Division forces captured a number of German prisoners of war (a mixed bag of regular Wehrmacht infantrymen and SS troopers), only to summarily execute them by machine-gunning them in fields. Reports from soldiers like Staff Sgt. John W. Fague detailed how American troops aligned German POWs along the roads and shot them in reprisal for the atrocities committed at Baugnez.

Some of the boys had some prisoners line up. I knew they were going to shoot them, and I hated this business.... They marched the prisoners back up the hill to murder them with the rest of the prisoners we had secured that morning.... As we were going up the hill out of town, I know some of our boys were lining up German prisoners in the fields on both sides of the road. There must have been 25 or 30 German boys in each group. Machine guns were being set up. These boys were to be machine gunned and murdered. We were committing the same crimes we were now accusing the Japs and Germans of doing.... Going back down the road into town I looked into the fields where the German boys had been shot. Dark lifeless forms lay in the snow.

Staff Sgt. John W. Fague, B Company, 21st Armored Infantry Battalion, 11th Armored Division

The Chenogne massacre became part of the broader narrative of war crimes committed during the Battle of the Bulge. American and British soldiers, outraged by the Malmedy massacre and other Nazi war crimes, allegedly acted on orders that "no SS troops or paratroopers would be taken prisoner but would be shot on sight." However, evidence of this policy remains scarce and debated. What is certain is that the commanders of some frontline units ordered their men not to take any SS troops alive.

One of the enduring controversies surrounding these events is the alleged coverup by U.S. military authorities. In the immediate aftermath of the war, there was considerable effort to prevent the full extent of possible U.S. war crimes from becoming public knowledge. The official U.S. government history dismissed claims of systematic killings of German POWs by American forces, attributing such actions primarily to "isolated incidents."

However, declassified documents and interviews suggest that senior military leaders may have been complicit in downplaying or concealing such incidents. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who sought to maintain the moral high ground of the Allies, requested full investigations into these extrajudicial battlefield killings but faced resistance from American units, which often withheld evidence or failed to cooperate fully.

Ben Ferencz, a prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, later argued that such actions smacked of a coverup, emphasizing that the truth had been suppressed to avoid tarnishing the Allied reputation.

The Malmedy massacre remains a stark reminder of the brutal violence that marked the latter stages of World War II. At Baugnez crossroads, 84 U.S. soldiers fell victim to the unforgiving cruelty of the Waffen-SS, their deaths a testament to the atrocities committed during the Battle of the Bulge. The massacre sparked outrage, leading to war crimes trials and the eventual exposure of the horrors perpetrated by both sides.

Today, the memory of the Malmedy massacre serves as a somber reminder of the cost of war and the need to remember the victims whose lives were unjustly cut short.