Ukrainian history is steeped in the lore of the Cossack Republic that occupied the lands around the Dnieper River in present day Ukraine. For 300 years the Zaporizhian Cossacks were a force to be reckoned with; alternately loathed and feared they acquired a buccaneering and mercenary reputation. They had their own political system run by the military and a legal code. The nation was organized into thirty-eight municipalities and several administrative areas governed by elected representatives who were all military leaders. The central government was run by an assembly composed of representatives who served one-year terms (and who were all soldiers) elected from the various districts annually on January 1st.

At various times Cossacks were claimed as subjects by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Turkish Khans, the Ottomans, and Imperial Russia who viewed them as crude, ignorant, and fickle. However, the Cossacks proved a difficult lot to rule and were, generally, allowed to govern themselves as long as they provided military aid in times of conflict. Consequently, at various times they allied with or opposed all these powers. Catherine the Great finally had enough of the unruly Cossacks and in 1775 ordered a surprise attack on the Cossack army that had just helped her fight the Russo-Turkish War. Stabbed in the back by the sovereign they served, the Zaporizhian Cossacks were scattered and disarmed. Some settled in the Danube Delta while others were allowed to join the regular Imperial Russian army. Interestingly the Russians today, as during Imperial times and under Soviet rule still generally view the Ukrainians as bumpkins and refer to them by the derogatory term Kholkhol (roughly translated means sheaf of grain stalks).

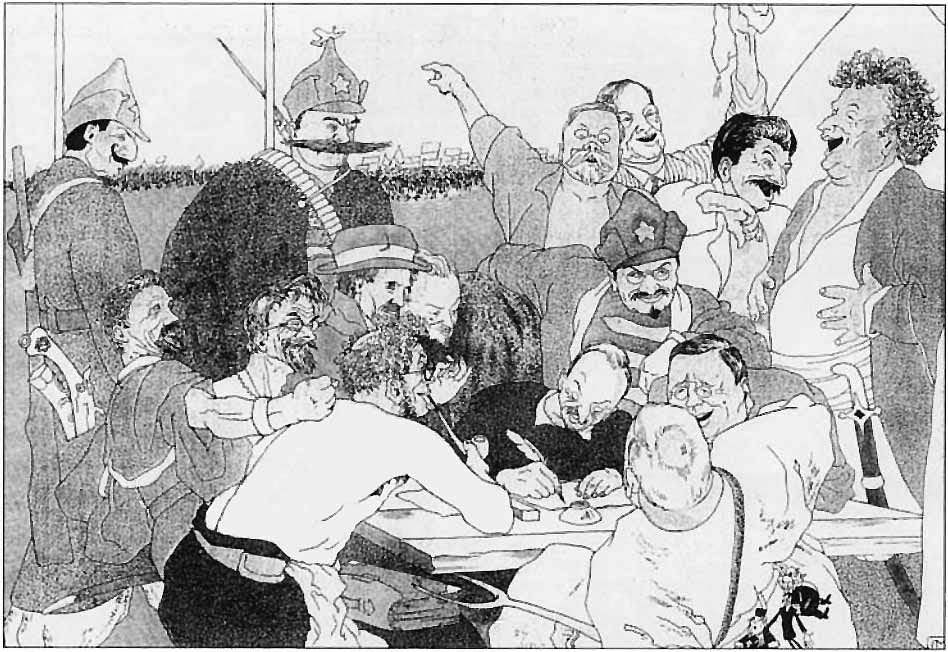

Ukrainian-born painter Ilya Yefimovich Repin was fascinated with the lore and stories of the Cossacks. In 1880-1881 he created what would become an iconic image in 19th Century Russian and Eastern European artwork. The painting, set in 1676 and titled Reply of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, depicts the victorious Cossacks composing a reply to the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV. The Sultan, who even after his army was defeated by the Cossacks, demanded that they submit to Ottoman rule anyway. The Cossacks, as the story goes, composed a vulgar and insulting response to the Sultan’s ridiculous ultimatum.

In 1889 Repin painted a second version titled The Cossacks that he wanted to be more historically authentic. Repin, who was an art student at the University of Saint Petersburg at the time, used a group of classmates and professors to pose as characters for his second painting.

The painting went on to acquire iconic status and was later used as Russian political propaganda in the revolutionary era of the early 1900s. In 1907 caricature artist Luka Zlotnikov satirized Repin’s painting, using it to lampoon the Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin and the Russian Duma in the magazine New Times (Novoe Vremya). Then, in 1923 a communist artist used the image to mock British Foreign Secretary Lord George Curzon and his proposed Soviet-Polish boundary.

In a modern-day iteration of Repin’s first painting, French photographer, and visual artist Emeric Lhuisset has recreated the image which features soldiers who are members of Ukraine’s 112th Brigade. The central figure in the photo is Roman Hyrbov, a Ukrainian soldier posted on Zmiinyi Island who told the skipper of the Russian warship Moskva “Russian warship – go **** yourself” on the first day of the current conflict.

On his Instagram account the French artist noted the importance of culture in the war. "While the war intended to conquer the Ukrainian territory is visible to all and its condemnation relatively consensual in Europe, the much more insidious war which is being played out around the control of history and culture remains very much unknown and many Europeans participate, often unconsciously, to the diffusion of this Russian colonial construction…”

Russian State Media Pundit Calls for Cultural Genocide in Ukraine