Nine Familial Exterminations

Historical Legacy of Collective Punishment

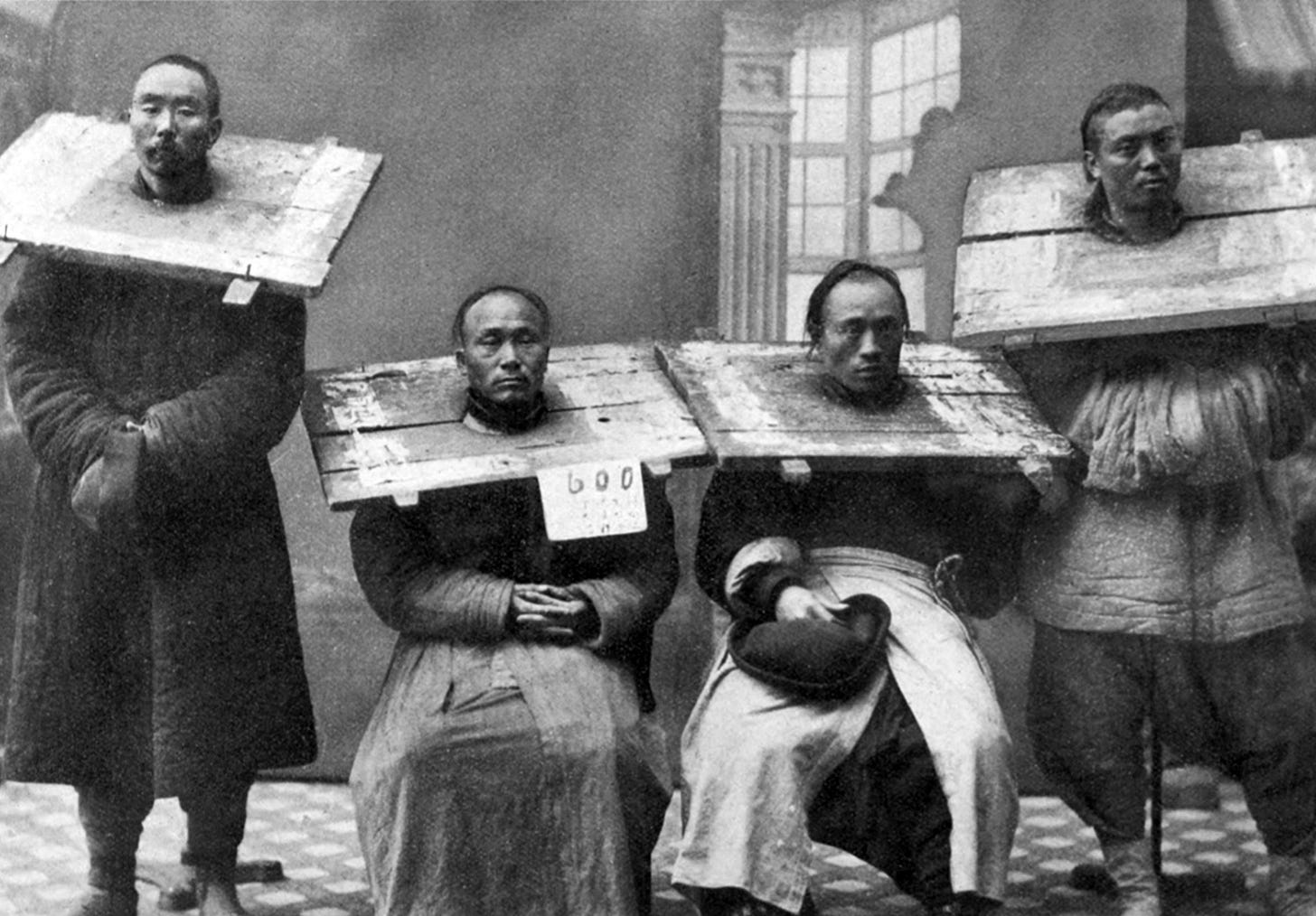

The Nine Familial Exterminations, also known as zuzhu (“family execution”) and miezu (“family extermination”), represent one of the harshest forms of punishment in premodern East Asia. Practiced in China, Korea, and Vietnam, this form of collective punishment was typically reserved for capital offenses like treason. It involved the execution of all relatives of the convicted individual, categorized into nine groups.

Scope of the Punishment

The Nine Familial Exterminations targeted a wide array of the criminal’s relatives, including:

Parents and grandparents of the offender.

Children and grandchildren above a certain age (younger children were often enslaved) along with their spouses if married.

Siblings and siblings-in-law, encompassing both the offender’s siblings and the siblings of their spouse.

Uncles, aunts, and their spouses.

Cousins, in some cases extending to second or third cousins.

The criminal’s spouse and their parents.

The criminal.

Historical Origins

The concept of family extermination is first mentioned in the Book of Documents, chronicling events from the Shang (1600 BC – 1046 BC) and Zhou (1045 BC – 256 BC) dynasties. During this time, military officers used threats of exterminating subordinates’ families to ensure obedience.

Spring and Autumn Period (770 BC – 403 BC)

Records from this era detail punishments targeting "three clans" (sanzu). One infamous case involved Shang Yang, a lawmaker in the State of Qin. In 338 BC, King Huiwen ordered the execution of Shang Yang’s entire family and sentenced him to death by quartering. Ironically, Shang Yang had introduced such harsh laws himself.

Qin Dynasty (221 BC – 207 BC)

Under Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of unified China, familial extermination became a tool for maintaining strict control. Crimes like libel, deception, and possession of banned books were punishable by this extreme measure. However, such draconian policies fueled widespread discontent and multiple assassination attempts, contributing to the dynasty’s swift collapse.

Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD)

The Han dynasty moderated the use of family exterminations. In many instances, emperors retracted such sentences, making the practice less common compared to the Qin period.

Refinements During Later Dynasties

By the Tang dynasty (618–907), family extermination was reserved for treason and rebellion. The Tang Code specified the death of close relatives, including parents and children over sixteen. The punishment became more regulated and less indiscriminate.

Under the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Kublai Khan extended the practice to include cases of corruption. For instance, after the assassination of Persian finance minister Ahmad Fanakati, his sons were executed.

Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368–1912)

The Ming dynasty expanded the scope of family extermination, targeting cohabitants, friends, and other non-blood relations connected to the criminal. One notorious example was the philosopher/writer Fang Xiaoru, whose family members, students, and associates were executed by lingchi (death by 1,000 cuts) by order of the Yongle Emperor for insubordination (Fang refused to write a speech for the emperor). The Qing dynasty continued these practices, as seen in the 1728 suppression of Tibetan rebels, where entire families of rebels were executed.

Modern-Day Echoes in North Korea

Although officially abolished in China by 1905, the principle of familial punishment persists in Communist China in “guilty by association” policies and in North Korea under the yeonjwaje (“association system”). Testimonies from defectors reveal that political offenders’ families—spanning three to eight generations—can be imprisoned or executed. These punishments occur outside the formal legal system, based on internal Workers’ Party protocols. Relatives are often unaware of the reasons for their punishment, and children born in prison remain detained.

The Nine Familial Exterminations highlight the extremes of authoritarian control, where an individual’s crime could result in the extermination of an entire family lineage. While rare, the punishment’s symbolic power served to deter dissent and consolidate rule.

Modern societies have largely rejected such collective punishments, recognizing their inherent injustice. However, their historical presence serves as a sobering reminder of the potential for abuse in systems where power is unchecked.

References

Confucius. Book of Documents, Shangshu: Bilingual Edition, Chinese and English: Chinese Classic of History. Translated by James Legge. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016.

Hawk, David. Concentrations of Inhumanity. New York: Freedom House Publishing, 2007.

McNeill, William H., and Jean W. Sedlar. Classical China. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.